… Le dollar trinque, l’or salue l’évacuation du risque de changement de cap monétaire et l’écrasement des taux réels à court terme qu’il provoque.

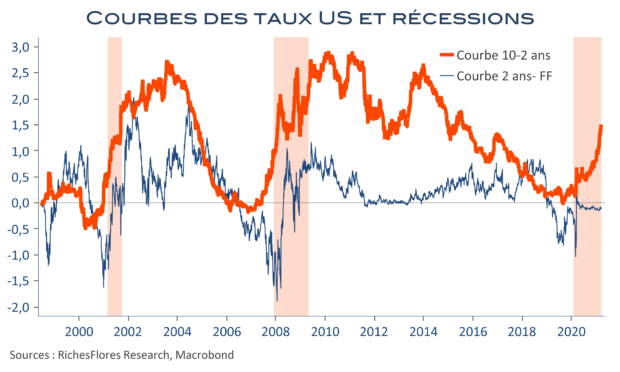

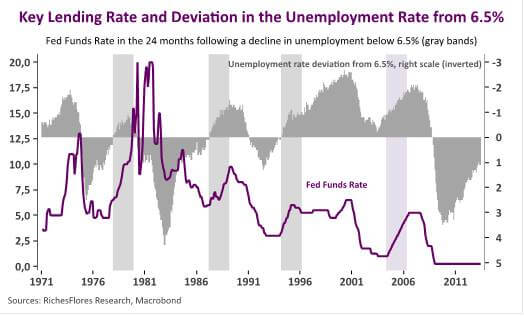

Pas de changement de posture, donc, de la part de la FED qui continue officiellement à voir dans la remontée des taux longs une réaction normale des marchés à l’amélioration des perspectives économiques, que ses projections confortent ; ses prévisions de croissance pour 2021 sont revues à 6,5 % l’an pour la fin de l’année contre 4,2 % en décembre. La pentification de la courbe des taux ne préjugerait en rien de la nécessité de changer de cap monétaire. À ce titre, J. Powell rappelle que le niveau des taux d’intérêt est resté très bas pendant l’essentiel du cycle passé, pourtant le plus long de l’histoire contemporaine. Le changement de policy-mix ne soucie pas davantage le président de la FED qui met en avant la nécessité d’une politique de soutien à l’investissement, qu’il se donne, manifestement, comme mission de faciliter par le maintien d’une politique durablement très accommodante.