Comme attendu, le PIB réel américain a progressé de 6,4 % en rythme annualisé (1,6 % non annualisé) au premier trimestre 2021. Le retard par rapport à son niveau d’avant crise est ainsi ramené à un peu moins de 1 %, qui devrait être comblé sans difficulté au cours des trois prochains mois. La reprise semble donc engagée et le rattrapage du troisième trimestre devrait suffire à assurer une croissance d’au moins 7 % en moyenne cette année. Mais l’économie américaine tient grâce aux béquilles gouvernementales.

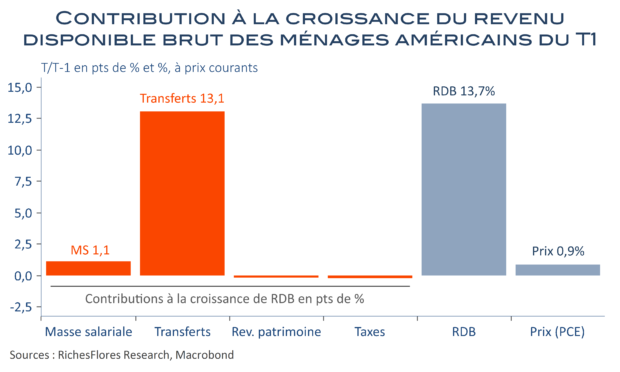

Les ménages ont reçu deux chèques de l’administration au cours du premier trimestre, plus de 2,2 Trn de dollars qui ont constitué 96 % de la croissance de leur revenu disponible, dont l’essentiel est allé à l’épargne et aux achats de biens, source quasi-exclusive de la croissance du PIB. Leurs revenus dépendront à l’avenir de l’emploi, des salaires ainsi que des prix et, sans doute, faudra-t-il qu’ils puisent dans leur épargne pour entretenir le rattrapage de la demande. De cela découlera le rebond plus ou moins rapide de l’activité dans les services, qui, contrairement à l’industrie, accusent encore un gros retard par rapport à la situation d’avant crise. Et de cela dépendront in fine les tendances de l’emploi et de ce qui fera la croissance avant que les réformes structurelles de J. Biden portent leurs fruits…