Download

When you get back from an overseas vacation, you’re often left with a bunch of small foreign coins in your pocket. You typically end up stashing them away in a junk drawer as soon as you get home, and this is precisely what I was in the process of doing after a recent trip to the U.S. when a penny dated 1964 caught my eye. I then looked more closely at the dates on my assorted pennies, dimes, nickels, and quarters. I even added my daughter’s coins to the mix. Soon intrigued by this journey back through time, we decided to group the coins by decade. What we found was startling: out of the 107 pennies left from our trip this summer, 3 were from the 1960s, 12 from the 1970s, and 11 from the 1980s. In other words, 24 percent of our lowest denomination coins came from years of double-digit inflation—when the coin mints apparently ran non-stop.

But what about the ensuing decades? Could we see the effects of the subsequent disinflation in our sample, given that our sample is necessarily biased by the lesser erosion in the supply of recently-minted coins? We had 13 coins from the 1990s and 18 from the 2000s. How could we possibly prove that once the time factor is taken into account, this is a much smaller proportion of coins relative to that from the inflationary decades? It seemed a hard circle to square. We were about to give up when we found some coins we had overlooked—our group from 2010 to 2013. There were many more of these, of course: 50 for a period of only 3.5 years—the equivalent of 142 coins per decade!

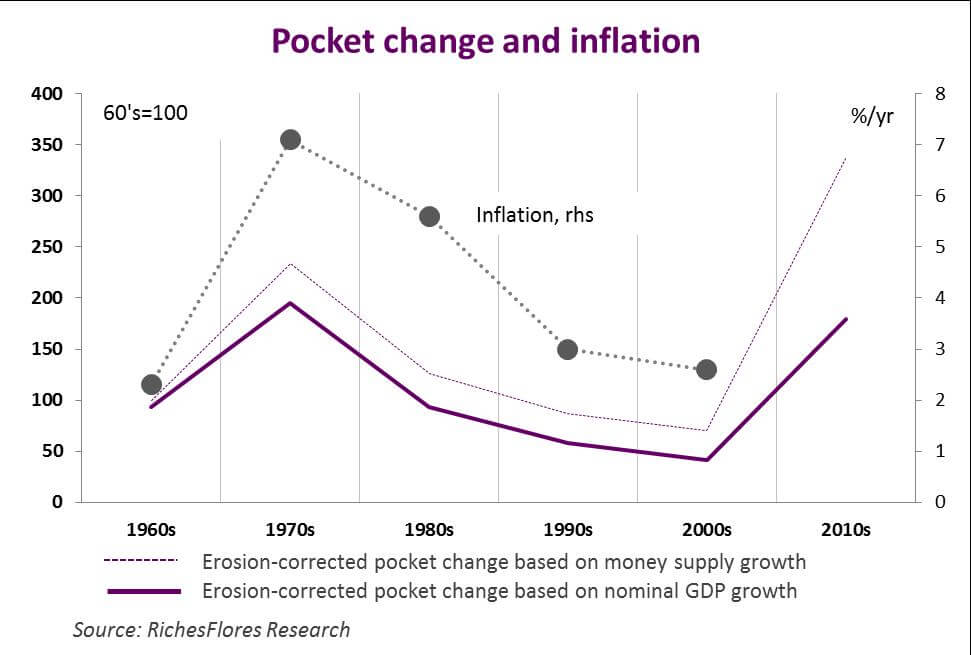

This shed an entirely new light on our figures. We realized that since we may safely assume the rate of erosion remains pretty much the same from one decade to the next, we can estimate the “erosion-corrected” size of a group of coins from a given decade by “reverse discounting” its actual size by an erosion factor. So we found a pen and did some back-of-the-envelope calculations. First we used an annual erosion rate of 5.5 percent, which was the growth rate of the M1 money supply in the U.S. over the period we were looking at. Next we used an annual erosion rate of 6.7 percent, which was the average annual growth rate of U.S. GDP over the same period. As it turned out, 6.7 percent was closer to what our pocket-change sample suggested.

Theoretically, this gave us a comparable, erosion-corrected total number of coins for each decade. When we restated our results using a base value of 100 for the 1960s batch, we found:

- The erosion-corrected total peaked in the 1970s, at 234 using the 5.5 percent erosion rate and 209 using the 6.7 percent erosion rate;

- The total then decreased steadily and hit a low, in the 2000s, of 70 at the 5.5 percent erosion rate and 45 at the 6.7 percent erosion rate;

- The total rebounded sharply for our very last group of coins, those from 2010–2013, reaching a new high of 318 at the 5.5 percent erosion rate and coming in just below the 1970s value at the 6.7 percent erosion rate.

As you may have guessed, we couldn’t resist plotting our results alongside inflation for the same decades. Unsurprisingly, the curves matched up beautifully.

So what’s the moral of the story? Given the pace at which the amount of money in circulation has been growing since 2010, the U.S. appears on track for high inflation once it pulls out of the crisis. And we stand by our prediction even though the process seems to be taking longer than expected. An era of rising prices is already a palpable prospect.