The wealth effect—the increased consumer spending thought to result from rising financial and real estate asset prices—is frequently cited as a key argument for renewed faith in the U.S. economy today. That faith, however, may soon prove to be misguided, as we will attempt to show in this paper.

Economists use the term wealth effect in a very precise way: to explain how household savings patterns shift in response to changes in household net worth. When net worth goes up, due to an increase in the assessed value of homes or to rising stock prices, for example, people tend to set a smaller share of their wealth aside—in other words, their personal savings rate goes down, leaving more money for consumer spending. The term wealth effect basically refers to this higher consumption.

The wealth effect was particularly significant during the 2000s. It isn’t hard to demonstrate, for example, that in every year from 1998 to 2007, rising property values alone shaved as much as one percent off of the U.S. household savings rate. This made it possible for consumer spending to grow faster than disposable income, which had slowed as a result of weak job creation. For one thing, the perception of greater wealth created by rising asset prices tends to reassure households and boost consumer confidence in ways that encourage spending. For another, in countries with highly developed mortgage markets, increased net worth improves household balance sheets and enables homeowners to borrow more extensively. The macroeconomic benefits often produced by these factors would, of course, be particularly welcome in the United States today, since the Federal Reserve’s policies have turned out to be more effective in driving up assets prices than in stimulating the broader economy.

However, a number of problems are likely to prevent the wealth effect from operating as in the past:

- The first, and by far the biggest one, is the current savings rate in the U.S. Because the processes described above don’t directly generate income, they can’t influence growth unless consumers dip into their savings. This means that the strength of the wealth effect depends to a large extent on how high the personal savings rate initially is. As it turns out, that rate was equal to just 2.5 percent of U.S. disposable income in April, leaving very little room, if any, for a further decrease.

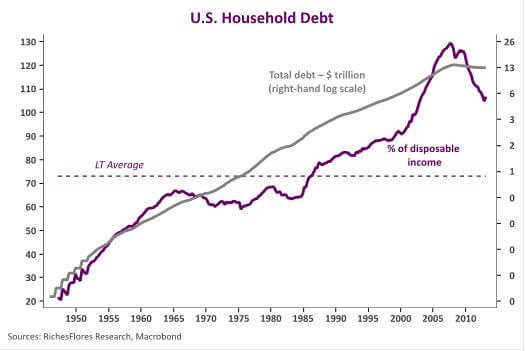

- The second problem hinges on how much debt American households already carry and on whether paper wealth gains will enable them to borrow more. The answer is: they won’t unless those households can afford a higher debt ratio—a rather improbable scenario at this stage. To understand why, it is important to bear in mind the distinction between the household debt service and household debt ratios. Due to falling interest rates—which have allowed U.S. homeowners to refinance their mortgages—and to extensive debt cancellation brought about by the wave of foreclosures in recent years, debt service payments as a proportion of disposable income have plummeted. This decrease in the debt service ratio has made more money available to households and has therefore been a major contributor to the recovery in consumer spending over the past two years. But this process can’t rightfully be considered a wealth effect, and since it is already behind us, it is unlikely to be much of a stimulus to future consumption. The debt ratio, which measures the stock of household debt as a proportion of income, is the only reliable predictor of household borrowing capacity. Unfortunately, it has remained stubbornly high: barely 20 percent below its pre-crisis peak, and thus well above its long-term average. So there is probably very little scope for a substantial increase in U.S. household debt—which in any case would be a bizarre development right after a debt crisis of the kind we have just been through.

All this, along with low job creation numbers, should make it clear why we have more doubts than most on the prospects for buoyant consumer spending in the U.S.